“Not for ourselves but for the Eternal family we live.

Man liveth not by Self alone but in his brothers face,

Each shall behold the Eternal Father

And love and joy abound.”

~ William Blake, Vala, or the Four Zoas

I was considering not writing anything for New Year’s —I have an unfinished term paper, and I am recovering from a head cold—but then I was seized by a terrible ‘fear of missing out,’ or as the Germans say, Torschlusspanik. Plus, I think it’s important to take advantage of symbolic occasions for reflection.

2024 was a difficult year. Arguably the most difficult year of my life, though I have a feeling they just get more challenging the older one gets, until one can’t tell the difference anymore. For the sake of this account, however, it was unparalleled.

In mid-January, I broke up with the man I thought I would marry. It was nothing jarring or explosive, certainly nothing we’ll both never recover from. It could most simply be sorted under the heading of ‘having different priorities,’ which is fairly typical when you’re in your early twenties and right out of college. However, scars from the wounds of tenderness linger, and it’s a terrible feeling to realize the man you would die for will one day have children that look nothing like you.

In the wake of this living nightmare, and laboring under (familiar) impaired reasoning, I texted my high school fixation, who pretended to come up to Philadelphia primarily to look at some Wyeths briefly on display at the Brandywine Museum.

About ten years before, we’d met at art school. I’d sit next to him on the large stools in class, and he would try to impress me with facts about String theory, of which he had not even a tenuous grasp, and I gave him books despite knowing he was dyslexic and would never read them. He was a solemn and taciturn teenager, and back then, his skinny legs in basketball shorts looked like Victorian lampposts. When he spurned me (several times), I bitterly clung to the consolation that much of Yeats’s corpus would not exist but for Maude Gonne’s repeated rejections: “The world should thank me for not marrying you,” she declared the last time he proposed, and at fifteen, I copied this into my journal…

Despite this, I continued to adore him intermittently and from afar for years. Consequently, my affection remained unmarred by the vagaries of real life. I entrusted him, without his knowing, with the singular consolation of believing the best of me in all things.

He was a large man, perfectly fit, with a mess of hair falling into long eyelashes and a wild mustache. He called to mind James Taylor on the front cover of that Rolling Stones magazine everyone’s mother kept under their pillow in the seventies. The first time I saw him in six years, he visited me in my apartment, and we spoke for twenty hours straight and barely slept. He told me about his father’s illnesses, his own struggles with alcohol, and how he spent his summers working on fishing boats in Maine. I heard all about his mad Maine friends who worked on the boat with him, particularly one man who was “wretched,” and had “evil eyes.” I heard chapter and verse about all manner of birds— puffins, murres, bald eagles. Apparently, I reminded him of an arctic redpoll, because they were “beautiful, and liked to travel all over.” This was very generous; I think I’d be more of a magpie, or the raven that drove Poe mad.

Late in the evening, we flipped through a book from a Chagall exhibition at the Philadelphia Art Museum. He said that one of his friends from art school had exclusively painted her and her boyfriend like Chagall—floating figures with craned necks—and that most people found it tiresome after a while, but he admired it. When I told him about Baudelaire’s dandy and his lobster on a leash, he instinctively replied, “Well that’s just silly,” as he studiously adjusted my many silver rings, turning them right-side up while my hand lay on his thigh. What would the lobstermen he knew think of Baudelaire? They would scoff at him! And rightly so…

Inexplicably, he thought I was the most intelligent person he knew—another holdover from high school adulation—but I thought him far more impressive than myself at the time. After all, he was a man brave enough to adopt the Wendell Berry financial model—live off your art, or die trying. I, however, am continuing my suspension from adulthood by attending graduate school for philosophical theology, whiling away my last few years of beauty and fecundity in Saul Bellow’s somber city. This entr’acte may be but another symptom of confusion..

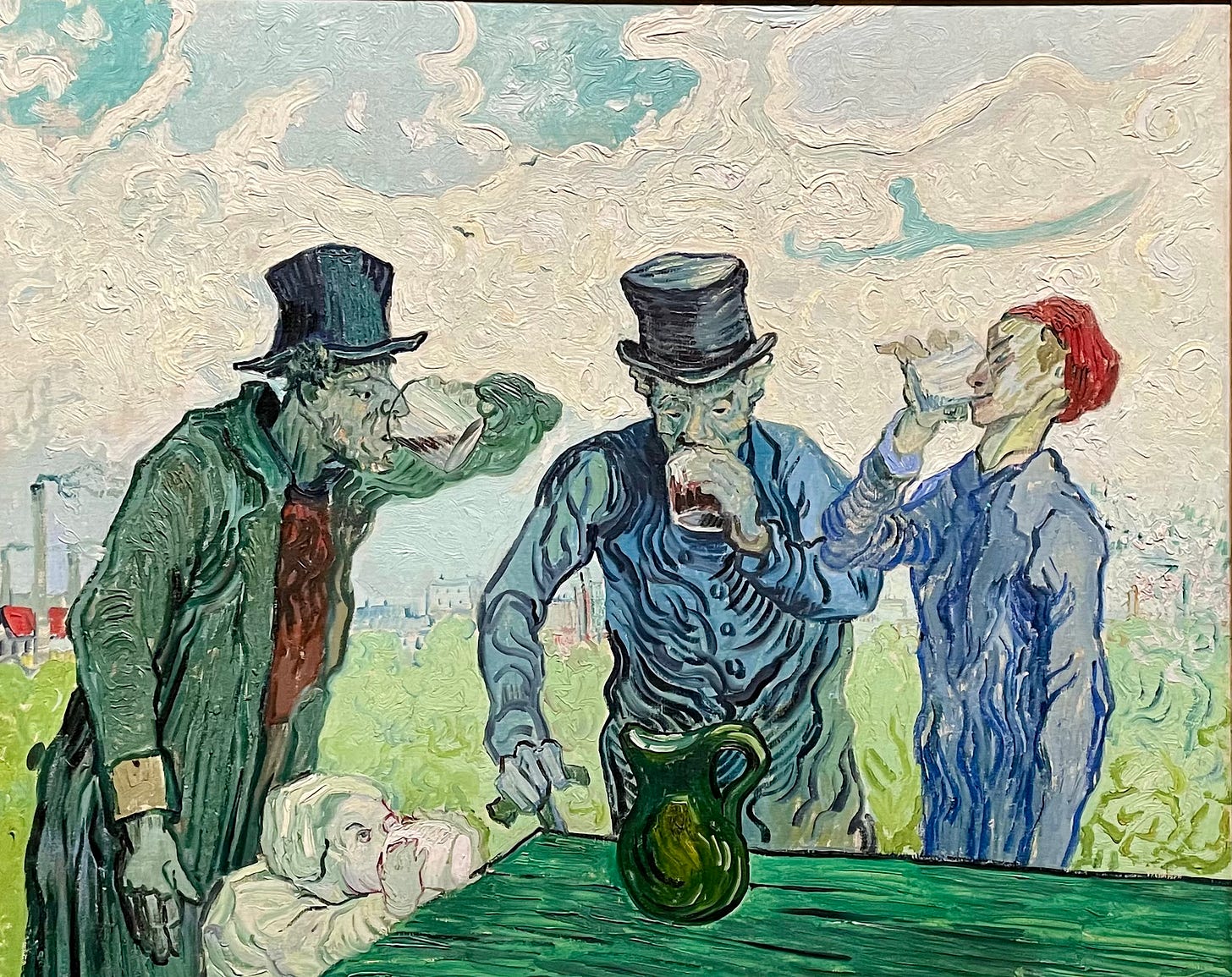

Anyway, it was I who introduced him to Yeats, Auden, and Eliot — the holy trinity of Anglophone Modernism. We laughed about how, now that he’d begun AA, he measured out his life with coffee spoons like Prufrock, instead of beer cans. He had a real love of language; after all, as an Irishman, that peculiar Joycean etymological mysticism was his birthright. Each morning, he got the Merriam-Webster ‘Word of the Day’ in his inbox. He had a curious penchant for French loanwords—he told me he’d been meaning to ask me how to use the word “milieu.” There was a whole month when he obsessively used “malaise,” to the utter bewilderment of his friends. “Ennui,” however, he thought sounded “too gay,” —the phonetics confused him.

He was sensitive in beauty and saintly in disposition; he had at once the humility of an autodidact and the heft of an apprentice. He wore ridiculous Birkenstocks and always had oil paint on his hands. His habit of donning cargo pants made me look at every construction worker with longing for weeks afterward. His father worked in air conditioning, for an HVAC company in Silver Spring. I was reminded of a summer I spent in Paris, in this shoebox across from l’Opéra Garnier, where it was ninety-five degrees at night. The ordeal made me seriously consider whether life was worth living before the modern luxury of central air.

He had no dogmatic ideas about ethics or the economy; he hadn’t taken up the mantle of any hollering prophet. He went about my apartment like it was a museum, with his boatman’s hands behind his back. After my four years at an Ivy League institution, he was refreshing—What does it even mean to be cultured? What does it even mean to have taste? Taste is a privilege! Plus, W.H. Auden believed the surest way to ascertain whether a young man had taste was if he believed he had none, and on this I agree with him.

The last time I saw him, he picked me up from the Silver Spring metro station right after his Friday AA meeting. I was waiting at the wrong level, at the lot for buses. Carpool and taxi was one above. I was reading Philip Roth’s My Life as a Man when I looked up to see him hanging over the balcony in a navy blue t-shirt — or perhaps it was cobalt, or azure— I am no painter. It was the dead of winter, and the sky was pitch-black. The picture was seared in my mind, this Adonis amidst concrete and fluorescent light.

He took his job as the coffee manager of his AA group very seriously. He showed me the keys to the church and the app on his phone, which displayed a meeting every thirty minutes. He adored the Big Book and its biblical rhetorical register; it was not moralizing so much as it was a galvanizing apology—reassuring, like a remorseful absent father. I read it after we stopped speaking, because of course, we stopped speaking — he shouldn’t have been seeing anyone in the first place, and it was a terrible idea for both of us to get involved with each other.

When it comes to fleeting, intense relationships, you take what you can get: the one day, or maybe two. By the second, the gold is flaking, because you know you can’t maintain this level of intensity forever, burning hard, hot, and fast, with a “gemlike flame,” like how Walter Pater described the short, obscene lives of the Decadents: “Not the fruit of experience, but experience itself, is the end.” Looking back, oddly, the best thing in my life at that moment seemed to be meeting someone I cared for who was barely hanging on. I was repulsed by the fact that we had mutually exploited each other at our weakest and most vulnerable, and I knew I couldn’t do such a thing again. Life requires the ability to make practical, complex decisions. It is not an eternity of listening to folk music in a dark room or posing for a portrait.

I met with a Dominican priest, which, for any non-Catholics reading, is the most intense kind you can find, one of the morose, scholastic types. According to him, my soul was on life support, my soul had been hit by a bus on the beltway, my soul had spent the night smoking a hundred unfiltered cigarettes… Fr. Dominic (yes, that was his name) encouraged me to pray no less than six thousand times a day. He also counseled me to get rid of all the images in my mind. How do you forget the images of a painter? What a terrific injustice. “Spiritual direction is about re-ordering your life,” Father Dominic said, “it is about handing your story over to God. You need to consecrate your life to the Virgin Mary and set your heart on the truth in order to gain a new perspective. God always offers signs, but you must surrender everything. You must break your attachments, and gain new anchors.”

The sessions were fairly exhausting. I was truly at rock bottom; I had lost the one person I really loved, and made a huge mess of the next person I touched—not to mention myself. Father Dominic eventually brought in the big guns, which turned out to be several minor exorcisms, part of which involved saying prayers to break ‘soul ties’ or deep emotional attachments. I cried a lot, through what I imagined were tens of prayers. There was a tremendous psychological overhaul; I felt like a criminal or addict in recovery, and my revulsion toward myself reminded me of the painter’s newfound disgust for liquor. I felt a peculiar sense of kinship with all those addicted to substances, given that we were all mired in the communion of regret.

One evening in February, I decided to sit in on an AA session in the city. The only open meeting I found that day was in a fairly grimy area, right near a metro stop. Most of the businesses looked run-down, and there were several suspicious sushi restaurants and tattoo parlors. It was not what I was expecting at all—most meetings in films are set in a church basement with gray walls and fold-out chairs arranged in a circle. This one was in what seemed to be a small community center building, and there were no lights on except lamps with neon pink shades. On the wall, there was an enormous poster of the twelve steps, and several smaller ones with proverbs like ‘Progress, not Perfection,’ and ‘This Too Shall Pass.’ The icebreaker was terrible; the question was “What is your favorite funk album?,” which was not something I had ever thought about. I pretended to agree with the man sitting next to me, whose answer was Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Going On”…

We then got into a meditation exercise, where we began by relaxing the body, to encourage everyone to develop the practice of being calm and sitting with themselves. I noticed an advertisement up about how no one is ever too young to join the fellowship. One angry man groaned each time he took a sip of his coffee, like he was throwing back a pint. After meditation, we shared testimonies. “Being sober doesn’t mean not drinking,” one man said. “But the more I come here, the less I want to destroy my life.” One girl talked about how there was no lasting happiness because of trauma, which I found terribly grim. An older man spoke about how his heart flat-lined after he bought wonky medicinal weed, and how he was just happy to be alive. He asked me for a lighter afterward for his cigarette. I had one I’d bought in Giverny, at the Monet museum, but I’d peeled off the sticker after someone I’d lit up outside the bar made fun of me for being simple. He was missing most of his teeth, and I didn’t want to let him limp away. One thing they spoke about, that I think about often, was that you forget how to trust yourself when you’ve given yourself over to your vices. You are afraid of self-reliance, and you are never certain of yourself. You must give yourself grace to get there.

After the meeting, I was so spent I decided to go to karaoke night at the bar. It was about the time that— as my favorite professor loved to say—“Proust would be heading to the boîtes.” A man named Lenny, who was near-blind, requested endless white wine from the bartender, who also happened to be a friend of mine. The lights were dim and warm, but Lenny’s sunglasses stayed on, and he twirled the slender stem of his glass with the dexterity of a maestro. A construction worker named George, who looked like a Mexican Elliot Smith went up to the microphone and shrieked, “I’m so drunk!” before slurring a homespun ballad.

At some point, I started to cry. Inexplicable joy intermingled with spiritual loneliness. Sometimes, your unhappiness feels like euphoria, and you rise above the earth like Icarus in that Bruegel painting. The only solace, I thought, must be the Mystical Body.

There were so many similarities between my Spiritual Direction and the AA meeting. In both, the masters teach the catechumens, and in both, there is the sense of “but for the grace of God, go I.” Once an addict, always an addict. Once a sinner, always a sinner— such is the nature of original sin. You might be wondering, “Is it really helpful to think of yourself as a criminal or an alcoholic when in spiritual darkness?” I would answer yes. Self-sufficiency is impossible and an illusion. To actually think of our fallenness as a sickness deserving of intervention is good, and so is enforcing bulwarks against it. You have to have accountability; you have to count every day since the day you last turned your life around. Can one ever love fully, without having to endure some painful lesson? It’s rare. I am reminded of a beautiful image in the Uffizi, Frederico Zuccari’s depiction of the proud in Dante’s purgatory, with their fingers bent downwards…

Alone on the sea, salvation is your own responsibility. Nobody else can save your soul. As an exercise, sometimes, I liked to imagine the contrapassos for my greatest sins…

This remorse ate me alive for several weeks. I was at my most desperately miserable. I was freshly graduated, alone, and unemployed with an $800 debt to the Philadelphia electric company and I had the next month’s rent over my head. I managed to find a job at a pizza restaurant, where I worked overtime and for minimum wage. My debts were chipped off bit by bit, but it got so dire I was getting light-fingered at the grocery store, which became yet another thing to mention at confession. One of the gentle highlights during that dark time was an unlikely friendship I formed with two people I happened to meet at the campus bar—the source of so much good and so much chaos in my life—a sweet girl from Buck’s County, PA and her friend, a third-year Penn student. The three of us went out a few times for drinks during that period; once both of them came over afterward for stovetop popcorn at my apartment. I don’t remember a single word we exchanged, but I felt so lucky, as if this was a fragile, precious thing. During a brief moment of clarity while smashing vodka-pineapples one night, I remember thinking about how Fr. Dominic said that God’s graces are sometimes delivered through other people.

In March, I got into graduate school at the University of Chicago, along with a funding package. I almost didn’t expect good news at that point, given that I’d resigned myself to what felt like a year of penance, but for faint glimmers of light through a keyhole. After that point, things began to pick up, slowly. I started dating a man I met on Twitter, of all places, a Catholic convert from South Carolina who also happens to be studying law at that one school in Boston. It turns out there is some laughter in this vale of tears. He took me to a wedding in Baltimore this May. It was the union of two Harvard Law students, both Princeton graduates—a fact that was mentioned no fewer than three times. The mousy, buck-toothed bride entered with a startled stare, as the groom clumsily wiped the tears from his eyes with his wrist. The sermon was about the cross and self-sacrifice— “Marriage is a slow crucifixion,” the timid priest declared—and ended with a dismal procession of gradually aging people. It was a touching, real-life illustration of why those allegedly at the tip of the Bell Curve are so lonely, and certainly cleared up any lingering doubts of mine.

One of the groomsmen had won the Harding fellowship at Cambridge, and was going on to study the sermons of Saint Maximus the Confessor on friendship— “As a Maximus scholar, I know he writes about how material objects, such as letters, are conduits of Grace—May our FaceTimes be a conduit of Grace!” He had recently broken up with his girlfriend, and when I reassured him that there were plenty more fish in the sea, he replied with vigor: “Ah yes! And I am a Pescator Mundi!” This, I thought, was the right attitude—hope!

I was silly this year. An idiot. I treated Jane Austen as fact and Brideshead Revisited as history. Fiction makes tantalizing promises, but the yoke of romantic sacrifice in favor of duty is utterly unglamorous. I learned about nuns from the French and prostitutes from the Russians, but real love from my own failures.

I’m sure there will be many more, though I’ve revised all my visions of Adonis.

Happy New Year to All.

I loved reading this so so so much! Your honesty is raw, refreshing and sets something alight in me - I truly can't wait to read more of your work. May this be a wonderful year for you and thank you for sharing these words.

Utterly fantastic. I was hanging onto your every word like a little boy clinging to his mother’s skirts. You write like no one else and with a heart quite alight to all the possibilities, earthly and otherwise, we have been privileged enough to have access to. Congratulations on your successes; I am so glad they found you. Thank you for this.