"J’ai traîné l’Amour dans le plaisir, et dans la boue, et dans la mort ; Je fus traître, blasphémateur, bourreau ; j’ai accompli tout cela que peut entreprendre un pauvre diable d’homme. Et voyez, j’ai perdu Satan. Satan s’est retiré de moi."

~ Miguel Mañara, O.V. L. de MiłoszWhen I was twenty, my parish priest, Father Kevin, was a large, pear-shaped man with a lisp and a military haircut. He was passionate about fair-trade coffee, and he had special handkerchiefs for both the liturgical calendar and baseball season. He was very optimistic—of the early patristics, he loved Origen the most, for his belief that every soul would eventually be reconciled to God. Too uncomfortable with the idea of a therapist (by then I’d read too much Philip Rieff), he became my Spiritual Director, and during our confessions I regularly gave him the workload of a full-blown psychiatrist. Despite this, he was conservative in his penances, settling on a single formula: “Say three prayers—one Hail Mary for yourself, an Our Father for your family, and a Glory Be for someone special.”

My true Virgilian guide, however, remains Saul Bellow, whose meticulous prose I discovered one summer, on the forbidden (slightly raunchy) shelf in my aunt’s bedroom. Bellow was there when I fell in love, when I fell out of love—after an injustice I would always return to his Herzog, where the protagonist, riffing on Keats, declares: “I fall upon the sidewalk of life, I skin my knees, I bleed..and what next? I get laid, take a short holiday, and then fall upon those same thorns in gratification and pain..”

John was his high school’s valedictorian, bespectacled, barely reaching the podium. From there he went to Princeton, which at that time held the title for best university in the country—maybe it still does. He studied History, and came out competent in five languages—if you count Middle English—and unlike his brother, worked at a Catholic think-tank upon graduation instead of Goldman. Until twenty-one, he was intent on the priesthood, but when the time came for discernment he was turned away with little explanation, and instead had to content himself with being a lay Dominican. The anguish of this rejection took its toll—human finitude was hard enough to reckon with without the added certainty that he would never be like the Medieval Scholastics, no matter how hard he tried. He took vows of chastity and temperance (though not poverty, thank God) and prayed three hours a day, setting up bulwarks for his bulwarks against sin.

The summer of my sophomore year I interned remotely at the Concilium Institute, the think tank where he worked, which was partly affiliated with my university. I was under the supervision of the woman heading their administrative affairs, and so spent my time filing budget sheets, writing reports, and sending emails. Tragedy struck when her sister fell into a coma, causing her to step back for weeks at a time. John filled in for her during this period, and, because the tasks I was assigned were not within his purview, we spent hours trying to complete them. Our calls became more and more frequent; while hunting for the names of donors and calculating expenditures, he told me stories from his freshman year of college, all of which occurred when I was in secondary school. He discussed Princeton’s eating clubs, heroic debates he’d won against gifted atheists, elaborate symposiums he’d organized on shockingly meager stipends, his favorite pilgrimage sites in Europe… I had the perfect job for accommodating this kind of outpouring, bent over my computer, cataloging four-digit numbers in infinite Excel spreadsheets.

Midway through the summer, I was summoned to Philadelphia to be the photographer for Concilium’s introductory seminar on soteriology. He insisted on meeting me beforehand to discuss my duties, and I remember nursing a strange sense of anticipation. It hadn’t occurred to me that romantic feelings could be involved, but that evening, when I blurted out that Pier Giorgio Frassati was the “sexiest almost-saint,” he looked momentarily jealous. The first day of the seminar, he opened with a meditation that I remember none of, because I was so enamored by his confident stance, despite his small frame. He had a monkish brilliance and temperament; he was like a priest in a retarded state, wearing his rosary ring like a wedding band, a frayed scapular positioned in the center of his narrow chest. Doing my photographer’s rounds, I lingered in the room where he sat discussing the theology of the body with fifteen-year-olds, trying to explain the notion that all organs have their ordained teleological function, his eyes in every shot veiled by the reflection off his glasses.

At the end of the day, I pretended not to know my way home, and we ended up sprawled on the banks of the Schuylkill with two mini bottles of Chardonnay, as he nervously discussed Ratzinger’s corpus. In my experience, it is not often papal documents are invoked during flirtation, but John believed there was an implicit link between Eros and pedagogy, that there was a sensual valence to teaching, being that it led one ever closer to the Good. Indeed, he had constructed a comprehensive course on Caritas in Veritate at his alma mater, in an effort to ‘bring truth to the academy.’ He wore a pink checkered shirt that didn’t need ironing—one of those staples of bachelordom—and light leather loafers, and I planted him with the first kiss he’d had in two years, which he later told me cast a shadow over his examination of conscience. “I don’t agree with James Joyce about Catholicism, but I do understand what he meant when he pointed out that kissing is a strange thing,” he said after the fact. “‘What did that mean, to kiss?’..” I began, “‘her lips were soft..and they made a tiny little noise: kiss’” “‘Why did people do that with their two faces?’” he finished. I loved the novella especially for its nod to Yeats’ He Who Remembers Forgotten Beauty, which I then recited: “‘When my arms wrap you round I press/My heart upon the loveliness/ That has long faded from the world..’”

He had different lists for brilliant men and women. First on the list was Elizabeth Anscombe, who could do no wrong. I can only imagine she served as the singular antidote to all the demoralizing encounters he’d had with the opposite sex until his first girlfriend at the age of twenty-five, a Chemistry PhD he dumped after a dispiriting performance of Prokofiev’s Romeo and Juliet. Walking around the Philadelphia Art museum, he’d contemptuously survey first the depictions of corpulent women; Fernando Botero, Picasso, the half-moon Impressionist asses with their tenuous slopes, then the sickly Schieles and Giacomettis. He gave me advice on research, graduate school, answering crucial questions such as “Oxford vs. the Ivy League for philosophy?” and “mini vs midi skirt for conference?” He insisted that he wasn’t a Puritan, telling me about his drinking (chiefly port), and ‘partying’ (reading Shakespeare out loud in Princeton’s empty theater after hours). He also believed, like Ronald Knox, that “a good sermon should be like a woman’s skirt, short enough to arouse interest but long enough to cover everything.”

His compulsion to run his hands along the back of his neck revealed his lean forearms, and the taut muscles of his bicep. To draw the exterior of the body you must have a sophisticated understanding of the interior anatomy; art school taught me this. Drawing from life trains your eye, and it acclimates to fleshiness here, firmness there. Nakedness, generally, I understood, and I had seen strangers undressed, but never him. I saw only the small eyes shadowed by the low brow, the disappearing edges of the heart-shaped mouth, everything below the neck concealed as the organs that rumbled in sleep.

What difference is seven years when you’re forty and thirty-three? Sixty-five and fifty-eight? Ninety-two and eighty-five? Unfortunately, it's a bit more conspicuous when you’re twenty and twenty-seven. He had seven extra years of reading on me, and we spoke similar foreign languages, studied the same discipline… So I rehearsed our conversations, trying to come up with things I knew he didn’t know, like Sanskrit poetry from the Middle Ages, French female playwrights, Medieval Sephardi Kabbalists. My lack of children or an advanced degree contributed, of course, to my youthful appearance, which I spent hours on, playing into being a sort of trophy thing, so embarrassed always, calling myself a “second year” when I met his friends instead of a Sophomore. I asked him, I sought him out, almost as if I was testing myself. Suddenly I blinked and all the men sizing me up were not twenty but thirty, and instead of “will she be a good girlfriend?” it was “will she be a good wife?” I knew gossip others didn’t, privileged knowledge that often only served to heighten and feed my anxiety, distancing myself further from others. My friends he thought were childish fools, which was galling, because I had made every effort to seem like I was so much older and wiser than I truly was. “It’s been a long-short life,” I remember telling him, but the company I kept had brought the façade right down. I went to daily mass and I called him before, on the way to, and after class; he was a disembodied voice I carried everywhere, as if Christ had come to earth and was living inside me, like I was some Immaculata.. I always felt like a child, a stupid thing, infinitesimal, in competition with God for him.

Because of my father, my admiration did not come easily; it was often forced into submission. When he found out about John, he gritted his crooked teeth, furious at this older man trying to lead me down the garden path to infinite children, spitting in the face of his enduring efforts to cultivate my mind, all of his dictées and reading lists. Before anyone else elbowed their way in, he was the first love of my life. He studied political science with Straussians at Harvard—he later regretted the lack of emphasis on Thomism—his ten years there culminating with a PhD on Grotius. For much of my childhood, he taught at the center for Religion and Foreign Affairs at Georgetown, which was one of my first insights into the strange world of academia and academics. In place of “How are you?” he’d sometimes ask “What are you reading?”, and I would curl up next to him like a cat, speculating on whether Albert Camus would have converted to Christianity, and whether Shakespeare was a Catholic. For a long time, the fact that he always knew more, that I could offer nothing new, was frustrating—now I expect it, as a comforting constant. I remember him saying, when I was a very young girl, that he loved God just a little bit more than my mother and I, and I not questioning it. He kept all our milk teeth in his bedside drawer, to my mother’s chagrin, as well as every found-gift of thimble or thumbtack. When I was a child, he’d read me C.S. Lewis’ fiction before bed, and it is his copy of the Four Loves ten years later that relieved me when I read within it that “the sins of the flesh are the least of all the deadly sins.”

I have always idolized great men, placing them on pedestals, wanting to tie myself to their shooting star and stave off oblivion. There was Andrew Lewis, my father’s mentor at Harvard, a nonagenarian with a thirty-year-old equestrian wife. He fought in the Second World War, almost forty years before her birth. Then there was the New York Times journalist who wrote seventeen essays on Edmund Burke, a wonderful stylist, afflicted with small teeth. He had an affinity for rooibos tea, and for years he kept his conversion to Christianity a secret, unable to convert to Catholicism because of his divorce. Adam Blum, the great bioethicist, was among my favorites; I wish Abraham could have given him some of his years, scattering them from the heavenly precipice. He helped found the Committee on Social Thought at Chicago, overlapping with Saul Bellow for many years. I recall vividly the disappointment in his face when I told him Bellow was my favorite novelist. “Oh yes, I knew him,” he said to me, “He’d come to my desk, and we’d exchange stories.” To me this seemed typical of Bellow; offering up snatches of old gossip, sniffing for some in return. “I read his Ravelstein about Allan Bloom, whom we both knew. What he did to him—awful! I despise the trafficking of intimacy.. ” This is a sentence that has remained with me since, every time I write. It is impossible to separate disloyalty from one’s own revision of history. Paul in his Epistles wrote I have become all things to all men, that I may by all means save some; Saul might as well have written, I have become all things to all men, that I may by all means save myself.

John and I would often discuss our lives through the prism of literature, speaking in allegories, so as not to pierce the veil of propriety with anything too direct, or too real.

“How would you rank your seven deadly sins?” I asked once, for example. “What vices are you more prone to?”

“Sloth, Pride, Wrath, Gluttony, Greed, Envy, Lust. In descending order,” he replied.

“Lust is the last one? What kind of man are you?”

“I’ve mostly been a monk and quite content with it..a Grace, surely.”

“Mine are: Lust, Pride, Sloth, Gluttony, Greed, Envy, Wrath.”

“That makes sense.”

“We’ve both placed Gluttony and Envy in the same order.”

“Pride too. We’re not very envious -- probably because of our pride. Like Dante in the Purgatorio.”

“Very true..so we differ on issues of Lust, Sloth, and Wrath-- not bad.”

“I'm fairly certain vices are bad. But yes, oddly similar rankings..although, frankly, Lust is so boring.”

“Why do you think so?”

“It simply doesn’t interest me. It’s a rather low vice.”

“Well, thanks; it happens to be my personal cross.”

“All crosses are good if borne gracefully.”

“True—and you will recall Dante considered intemperance in the matters of the flesh the least of all deadly sins..”

“He considered it vulgar too, but I suppose so is the Vulgate..”

That summer, I went to Paris to study with Michel Durand, a famous professor of Medieval philosophy at the Sorbonne. John was familiar with his work, in fact, Durand had just done an interview with Concilium the year before. As soon as we’d had our first meeting, I called John to relay every detail, straining to assess whether I’d made a good impression, whether I’d quoted the right encyclicals and Jewish mystics. I would consult him every time I hit a hurdle with Anscombe, which was often, sitting in Le Café de Flore, PDFs of the Summa and Intention open at the same time, the French people around me dismayed by my lack of sartorial elegance.

A week before I left, he flew out to see me for a single day. A total of only thirteen hours in Paris, so he could avoid spending the night with me, which would have been the height of impropriety. Within ten hours of picking him up from the airport, I had to send him back again. We only had time for a quick lunch, and the only Mass being celebrated was an evening Mass entirely in Spanish. It ended at half-past five, his flight left at seven thirty, and it was a forty-five-minute journey to the airport from where I was staying, so we compromised on leaving at five on the dot. Unfortunately, like the glamorous women she is often compared to, Paris is always behind schedule, and this evening was no different. John refused to depart before communion, so we ended up leaving late, giving him fifteen minutes to get to his gate once he’d reached the airport. I was irate, asking him, “Would you simply have slept on the street had you missed your flight? Would you just have paid for another one?” and “Is it really worth it— missing your flight to another continent for twenty more minutes at Mass?”

The answer to all of these questions was “Yes.”

My last meeting with Durand, he had me for tea in his apartment, which was on a street named after a twentieth-century jurist in the 16ème arrondissement. I had brought him a gift of an expensive wax seal, which he placed on the table, next to a bowl of madeleines and a pot of green tea. Since this was farewell, we dispensed with dry philosophy and intertextual comparisons, and his wife Françoise joined us, ensconcing herself between two plump cushions. Conversation drifted here and there, and, as is wont to happen with Catholics, settled on a discussion of our mortality: "Quand on est religieux, quand on vieillit, on se rend compte qu'on avance vers quelque chose—ou plutôt envers quelqu'un," mused Françoise. Michel nodded solemnly, "Nous savons que nous n'avançons pas envers un trou…" This simple meditation led to the most perfect, peaceful silence… In the end, what more would I want, than to be sitting with my husband, knowing that I am fully understood?

John was so perfect and new to me, like an exotic species. A pure and undefiled man, fighting the monotony of this engorged city. Meanwhile, I had prematurely wrenched aside the curtain of knowledge to betray the nakedness of desire, revealing Aphrodite in oversized knickers gathered about the knees, and shy, curled toes.. Looking back, I cannot help but think that I have mortgaged a quiet life of conjugal love and purity for a body marred by New York City pop -up shop tattoos, inked by men who studied Bosch in art school. All I wanted was to avoid being trapped in the last panel of his triptych, impaled mid-coitus amongst the pig-faced, voluptuous dead. I still remember John’s slight frame, teaching, standing authoritatively, imposing despite his stature, in front of the painting of the skull by Holbein the Younger. The asymptotic trajectory of Catholic courtship, getting infinitely close, but never joining, cannot work for me. I am too handicapped by my fear—I wanted not a life of ritual but a life of comfort. And so, I uttered a valediction for an entire future, awed at the audacity of the so-called Catholic Imagination. Women everywhere should be sure that their ovary Russian-Roulette is in revolt against their fragile, best-laid plans.

When it ended I told him,“You changed my life” and he replied, “You were my life,” never missing a chance to one-up me, it seems. “But I suppose it didn’t matter at all, then,” He said, refusing to meet my eye. “What do you mean it didn’t matter?” “Well it’s over.. It can’t have mattered that much.”

This was not the farewell I was used to from men my age. I was accustomed to utterly emotionless delivery: Of course I’ll never forget you and Of course a part of me will always love you, as if they were guessing the right responses to a police interrogation. But now, even when it was fresh, John offered no generosity, no tenderness. In what world is it most Christ-like to deceive? To manufacture? To contort? And all the while offering his pain up to Christ? “You’re not a martyr, you know. Stabbing yourself, just to cry to God,” I said, sneering, incensed. I wanted to hit him back with the same Dante he’d always quote to me: “Maggior difetto men vergogna lava”, /disse ’l maestro, “che ’l tuo non è stato; /però d’ogne trestizia ti disgrava./ E fa ragion ch’io ti sia sempre allato..”

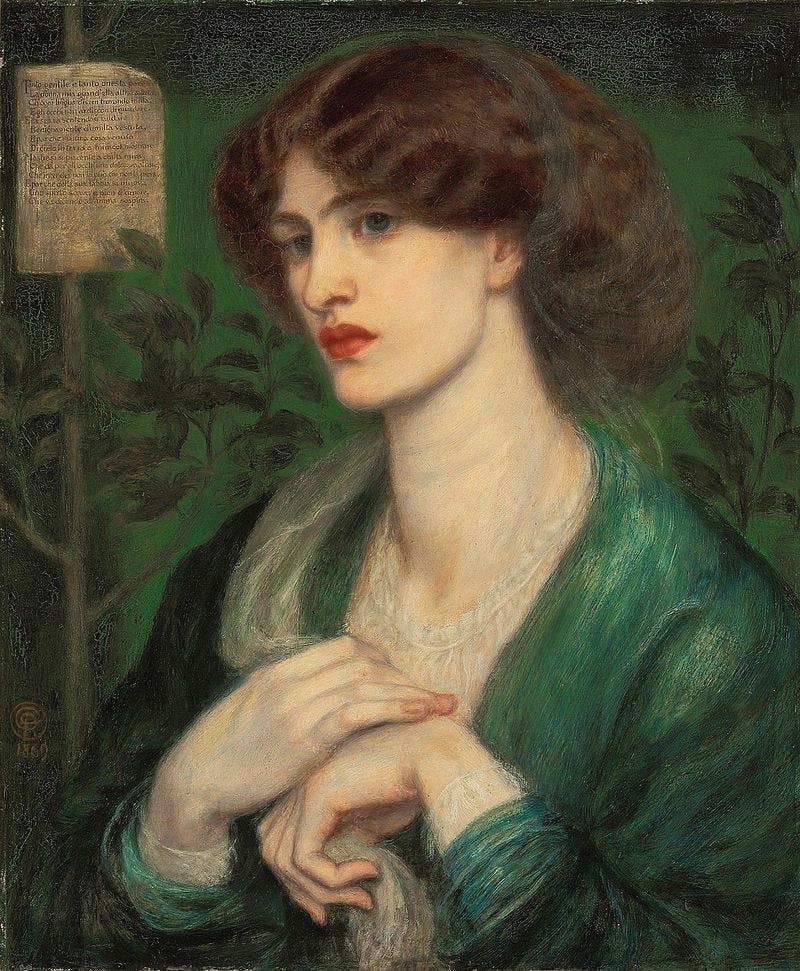

Nothing can prepare you for when that fever of adulation is over. The promise of the greatest joy imaginable, happiness in size seventy-times-seven font—dashed. I left him in his office, reading Plato’s Symposium, alone with his bust of Aristotle, innumerable essay collections and Milton readers, some of them with my love letters and postcards inside. He had a print of the Rossetti Beatrice hanging up opposite his Dante, with her pre-Raphaelite pucker, and her glazed, dull eyes. Stupid bitch, I thought. I would never be his media naranja, the other, imperfect half of his orange; I had existed for too long in a liminal space, as a sort of mistress to a man who didn’t have a wife. His idolization of mystique had led me to always conceal things for his beguilement, and I was left so immaterial and shrivelled, so like a waif.

In the days that followed, I came up with excuses to call his friends, leaping at such opportunities as birthdays and promotions, to try and justify my decision. None of them replied, except for one, a classmate of his from Princeton who was finishing Medical school in Kansas City. Unbeknownst to me, he and John were no longer in touch, largely because he’d given up on converting, content with Episcopalianism and its indolence. I told him everything, every admission its own little act of treason, and when I was done he sighed, a long, sugared sigh. “I’m so pleased for you. That you’ve emancipated yourself. We’ve advanced technologically, economically, medicinally—why are we clinging to a standard of purity that was a tall order even six hundred years ago?” I was silent; I didn’t believe in the invocation of date and time as a point of view, or that our living in the twenty-first century precluded the validity of certain habits, or beliefs. Like Gabriel Marcel, I did not believe that Time or History were spaces containing fields of unequal quality, but I listened anyway, happy at last to be vindicated, on some small plane. “How can someone say to you, ‘You’re the Virgin Mary to me, but now get out of my life!’?” he continued, “It’s a bastardization of Diotima’s scala amoris; it’s like trying to climb up the ladder, but someone is punching out all the rungs below you.” “Yes,” I replied, “a bit like that,” but really, he was making me doubt myself, appearing so like a split-tongued, Miltonian Satan. I thought of the circle of the virtuous dead in Limbo, who were there because they couldn’t hope for anything greater than an afterlife of drifting. Perhaps it was I whose vision was narrow, I, of so little faith.

Burlesque dancers have it all wrong, I tell you. No one, in their heart of hearts, wants someone for whom the habits and patterns of love and courtship are mechanical, rehearsed, and well-oiled. If you truly love someone, you want them to be all yours! And no one just wants sex. Even sex, as the great Herr Doktor Adam Blum says, is not just sex… I have been ignored by these beefy-necked men with an eye for prominent assets, ample breasts presumably reminiscent of their mothers’ tenderness. What is with these men and their obsession with voluptuousness? I never expected University to be so full of these cosmopolitan Botticellis with their silicone pre-Raphaelite tits, but maybe I am just bitter. My first boyfriend, who cheated on me with a Chinese exchange student and called me the next morning to describe it in detail, made me insecure for years. John telling me that he saw another beautiful veiled woman at a Novus Ordo Mass who he then looked up on Facebook was tantamount to the same betrayal.

Ultimately, all these men seem to want is beauty. “When you love someone, you’re supposed to love them body and soul,” John said once, “I don't think physical attraction is any more superficial than attraction to intellect; beauty fades, but the mind does too.” Truly, supremacy was impossible. I felt I had to compete with all the women of his future, this pantheon of possibilities, all lined up in Mantilla veils.

I had jeopardized everything, because of some mysterious pagan rot that had already seeped into me, through some error of formation. It would all be so simple if I’d had a vision like St. Teresa, whose heart was pierced by the Angel with a dart of love. If the erotic desire fades away, as we are told it ought, how does that make love deeper? I imagine it more like shingles, gradually falling off a decaying house…

Dante’s solution of courtly love, of clinging to the imaginary woman, is entirely unsatisfactory to me. You can nurse and live with your illusion forever; in real life, she is demoted as soon as she trips and falls from the pedestal of goddess. But even Dante would be ashamed of the Catholic academic landscape, men and women who eschew questions of globalism and terror, to insist that the Enlightenment teeters on Thomas Aquinas’s paunch. Perhaps John, too, would always want to stay shrouded in the Catholic academy, that little microcosm for an imaginary world. The Turris Eburnea hasn’t bent itself over, hasn’t toppled to the ground. It’s built a moat around itself, strengthened its barricades and buttresses, receding further and further out of the sight of the Volk. I imagine him, idle in paradise, the Divine Artificer, thinking about twentieth century life, a divine comedy all its own—Albert Camus, among the virtuous dead in Limbo, Harry Truman and Richard Nixon in the seventh and eighth circles, respectively, the Tory wets being chewed by Satan.. Fixed in my mind is a still shot of Bellow baring his coffee-stained teeth, exclaiming, “I have suffered,” while laughing from his slim stomach; “fucking his way to Hell,” as John put it.. I wonder where Bellow is. Purgatory, I should hope—one must not underestimate the extent of God’s mercy.

When it calls for it, I lay bare my tools like a roadside cobbler or a street-side caricature artist, yet I am always surprised by how few add up. I can’t write poetry; I never was good at verse. Too wedded to derivative rhymes, aping Yeats, Auden, Eliot, the Holy Trinity of Anglophone modernism. Auden’s melodic levity comforted me most, with its lifting cadence of an Anglican hymn, although I loved the fact that Eliot employed obscure references in his poems sometimes just for the sake of it. “The reason poetry is garbage nowadays,” John would say, “is because it is no longer a work of toil.” Toil belongs only to the sadists, the masochists—the religious. Months later, I recall that, of the war poets, he loved Wilfred Owen’s “Strange Meeting” the most, only because it was the most “Dantean,” or Dantesca, in his mother tongue.

How are you supposed to live your life with this burden? This suffocation? There are things that do not fit into the age-old cycle of birth and death. Technology, machinery, does not bury the dead. We cannot say goodbye; the psychic presence, the imprint is forever, and it is against our human nature to want something finite, if we truly love someone. “It’s all those French people you read,” my advisor-cum-confidant would tell me, “All this Balzac, and Flaubert, and Zola.. Was a single one of them happy?” You are what you read, it seems, unfortunately; “Per più fïate li occhi ci sospinse/ quella lettura, e scolorocci il viso;/ ma solo un punto fu quel che ci vinse..” I understand now why Saul Bellow kept such an assiduous schedule, why he only wrote in the mornings. As the day wears on, the excavated memories begin to wear on you, surprising you. We swing from one end of our psyche to the other like trapeze artists, associating present detail with forgotten detail... But the ordinary thrill of the day, the unbroken course of the sun, and the inescapable demands of our corporeality—clothe me, feed me, propel me—end up dispelling these thoughts, slowly, but surely. Gradually our bodies, stubborn and demanding like children, cannot be ignored anymore but require the full force of our attention, and by nightfall, these echoes have been shelved again, sorted into their mysterious filing cabinets, and put to bed.. “Tu proverai sì come sa di sale/ lo pane altrui, e come è duro calle/ lo scendere e 'l salir per l'altrui scale..”

Such are human things, said Byron, of how the Nero who defeated Hannibal is not so much remembered as the Nero who burned down Rome. The sheer burden of replaceability is sometimes too much to bear—the idea that there should live on in him only a false memory of me, as my most wretched, perverted self. Being once the foremost thought, and then the most forbidden, a willful expulsion, was agonizing. Looking through the window, at all my past lovers, I think, “That should be my life”—but it’s not even the life I want. I just don’t want to get left behind, outside of memory, carefully excavated by misery. I imagine them perspiring while making love, sweat running down in rivulets, like it would have for Jesus during the trudge to Golgotha.

There are mysteries I believe in. There are mysteries upon which my life depends. And then there are gratuitous mysteries—mysteries fabricated out of fear and duplicity. Those I abhor; those that conceal nothing. But I see His eyes in everything, the eyes that go reaching back into Infinity. I saw them in the tenderness of pliable joints, stiff, curly hair, and a small, open mouth; “conosco i segni dell'antica fiamma..” Bellow, in a letter to his friend about his third wife, Susan, (twenty years his junior) once said that; “You’ve got to take a young woman, and only a man can make her grow up.” For all my sensibilities, I think that’s true—For in much wisdom is much grief: and he that increaseth knowledge increaseth sorrow. But this is a constructive torment—we turn our subjects into symbols, like scratch-off lottery tickets. All this suffering had better make me a million dollars, because I’ll bet on it, one day, as if there’s no currency so sturdy as my own soul.

In the end, you can’t take much with you, but you’re always left with one perfect moment. Just one, though it may last a hundred hours. And what is that, in comparison to a lifetime? A lifetime of devotion, of spiritual and physical unity, of birth and death, of sacrifice, pension funds, retirement plans, of filing taxes jointly. I can’t imagine my father ever pining for a younger woman he loved when he was twenty-seven. In my own life, too, I demand absolute allegiance—I want a virtuous man, and a virtuous man must necessarily denounce all forerunners. But I also know that mercy must work alongside justice. I recognize the invisible shackles of limited expectations, just as I know I am not a victim of my own paltry success. Even still, I am a generous landlord; I let my tenants overstay their lease in my mind, and even when I evict them, they erect dwellings in its periphery, sometimes managing to crawl back in.

Amazing. I converted to Catholicism while at Princeton Theological Seminary a few years ago, then stuck around to do Catholic campus ministry at the university. So much of this perfectly captures the young East Coast Ivy(-adjacent) Catholic scene, which draws and repels me by turns. As a latecomer to the great books and the Church, it is easy for me to think that if only I had been raised steeped in Thomas and friends, I would have made less mistakes and be farther along in the areas I care most about (ie family and career). But the reality is that you can’t out-parent original sin. Even (although I’m skeptical of this as I say it) by reading lots of Lewis with your children. Phronesis REQUIRES experience. This is why Aristotle thought you couldn’t have practical wisdom until you were in your 30’s. Being raised with several languages and Dante on my tongue may have helped—maybe. But there is nothing in the mind that is not first in the senses, and it still would have taken me some time to take in the world and my misuses of it to actually understand what the greats were telling me about sin and virtue and grace.

Anyways this occasioned a lot of reflection for me. I’m looking forward to reading your other stuff. Glad you’re here and writing!

you have given voice to the insides of my mind! bravo!

i see so many parallels between your story and mine - [i have] a lawyer-cum-academic father, an austere and devoutly religious upbringing (replete with early morning bible readings with the rest of family), a brief dalliance with a figure of authority in my life, 8 years older than i

after 4 years of cutting religion off from my life, i've decided to reclaim it for myself, sans filial obligations. i often attempt to analyze it from a secularist lens (unsure if i truly believe in a christian God, but will gladly go through the motions of communion, prayer, worship etc.)

cool to read another 20something's thoughts on faith! religion! spirituality! in a world and a time when such discussions are stigmatized. happy to subscribe!